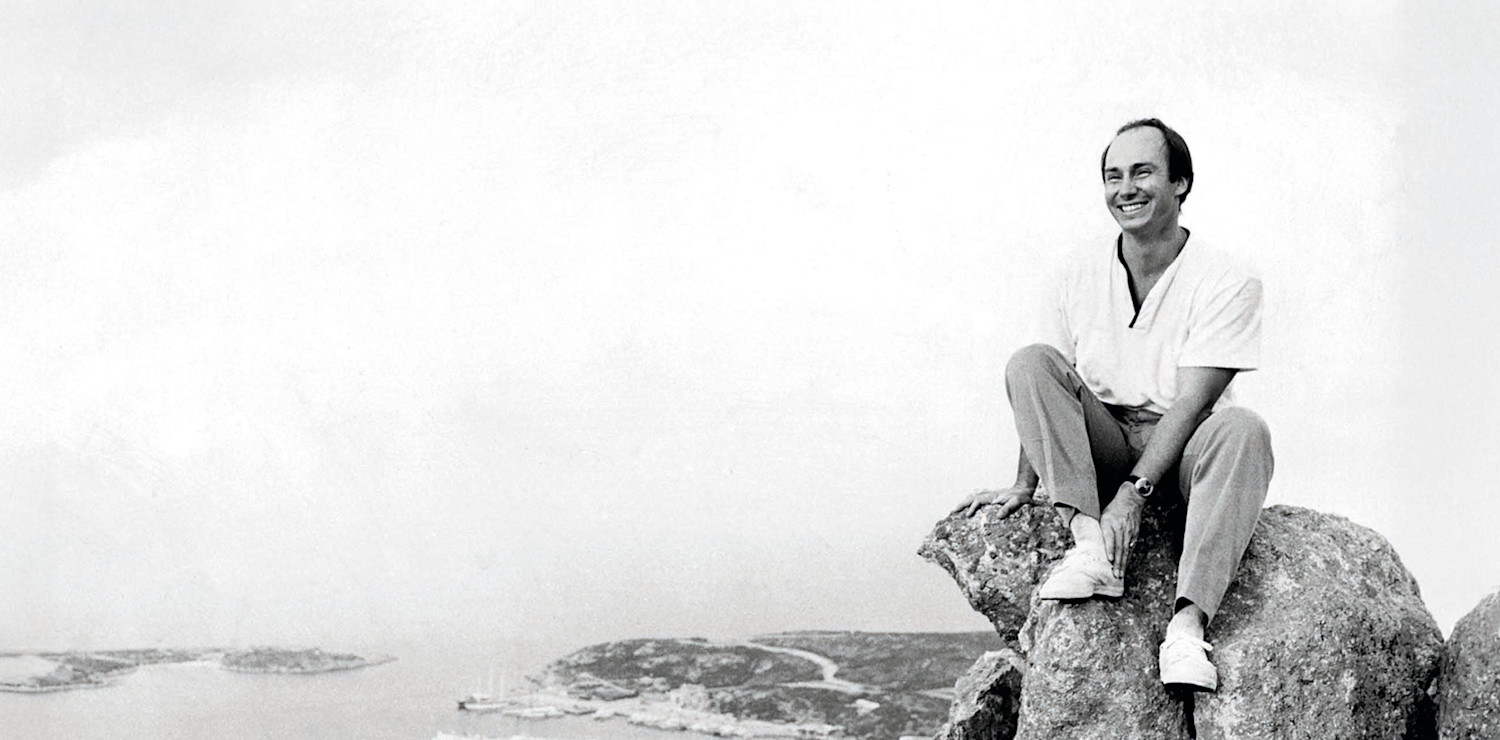

Costa Smeralda®, the origins of the project in the words of Prince Karim Aga Khan IV

From the archives of Costa Smeralda Magazine, a 1987 interview that reconstructs the birth of a legendary destination

Height, the Costa Smeralda® dream turns twenty-five. Many know this tourist destination, but few know who discovered it and how the idea was born. Can you tell us how it was discovered?

Towards the end of the 1950s, I decided it would be appropriate, during the years of decolonization of East Africa, to establish a publishing organization. [...] The goal was to create a consortium of newspapers that could participate professionally and financially in the initiative, with the support of a group of financial institutions. One of the newspapers was the Sunday Times, then owned by Lord Thomson, whose bank was the S.J. Warburg group.

It was during a breakfast with the bank's top management that one of the directors, Mr. Duncan Miller, spoke about Sardinia, which he had the opportunity to visit while overseeing a World Bank program in southern Italy. The program focused on the south of the island, but during an excursion in the northeast, Mr. Duncan Miller discovered an area of extraordinary beauty. On his own initiative, he proposed to some friends in the banking world to participate in the purchase of land in that area, where they could build villas for personal use as summer residences. Some of his friends accepted the proposal, including Patrick Guinness, my half-brother, who had already visited Sardinia. Mr. Duncan Miller showed some photographs of the area, taken in the summer.

The images were particularly beautiful: extraordinarily clear sea, no buildings— it looked like paradise on earth! Thus, a small syndicate of individuals was formed, participating exclusively on a personal and private basis; among them, Lord Crowther, owner of The Economist. Even though I had never set foot in Sardinia, I agreed to join the company. My investment in this venture was $25,000. Naturally, I decided to go see the land I had partially purchased. It should be noted that this was a syndicate with a corporate structure that gave all members equal rights to the property—about a dozen people co-owning an area of several tens of hectares.

In December 1958, after an uncomfortable ferry crossing from Civitavecchia, I arrived in Olbia for the first time. I stayed in an even more uncomfortable hotel near the railway line, at the entrance to the commercial port of Olbia. At 4 a.m., I was awakened by the movement of the shunting wagons for the port. To reach the area I was heading to, it was necessary to leave early. The road was a country path, and after four hours I arrived by jeep in Abbiadori. From there, I continued on foot toward Capriccioli. It was cold, rainy, and windy. Upon reaching Capriccioli, it was impossible to identify the land we had purchased. There was no source of drinking water, no telephone within several kilometers, and the jeep trip from Porto Cervo to Olbia and back took no less than eight hours— a real challenge just for daily supplies.

Romazzino Beach

Romazzino BeachSo, I was not the one who discovered this wonderful area; on the contrary, my first experience was negative in every respect. I bitterly regretted investing that $25,000, which was a significant sum at the time [...]. I realized I had been poorly advised by very unrealistic people, because at least some, if not all, members of the syndicate must have known that it would have been impossible to build any kind of summer residence in that area. My first thought was never to return to Sardinia. But, to avoid regretting my entire investment, I decided to delve deeper and try to understand what Sardinia was. [...] In the following spring, I made the same journey: by air to Rome, ferry to Olbia, and then by jeep and on foot to the area that today forms the consortium territory. The sun was beginning to warm the land, the sky was clear and intensely blue, the Mediterranean scrub was lush and dotted with yellow broom flowers; the sea sparkled on the shore. The landscape seemed to whisper to me: “Do not judge me too harshly for how I appear in winter; now I am wearing my spring costume, so come back in the summer. You will find me even more attractive!” The message was enticing, but the environment offered absolutely no services that would allow someone to build a summer residence.

The “call” was so strong, however, that I returned that summer. With some friends, we set sail [...] from the French Riviera. As soon as we left the port, we encountered rough seas with a Force 8/9 mistral. After several tens of hours of difficult navigation by day and night, and after a challenging passage through the Strait of Bonifacio, battered by the violent wind, we finally arrived in the bay of Porto Cervo, which appeared to us as a paradise of peace and tranquility. The next day, the wind subsided, and the following day nature presented herself in her summer attire: warm sun, incredibly clear and sparkling sea, white beaches, probably untouched for centuries.

My relationship with Sardinia, therefore, was not love at first sight, but since then it has been a passionate affair in every sense of the word—emotions, feelings, and future evaluations.

The formation of the Consortium was one of the first important steps in this initiative. Why the Consortium?

The beauty of the landscape, dressed in its summer elements, convinced me. Despite traveling extensively worldwide for my international commitments, I had never seen places as attractive as this. I did not want to keep my involvement with this land a secret. Gradually, more and more people came to Porto Cervo, declaring their love and making emotional and material commitments. Being all so romantically involved, it was almost immediate that, together, in pursuing our goals, we would take the necessary precautions to protect these unique and unrepeatable characteristics of extraordinary beauty.

At that time, the idea that this area could one day become a tourist destination did not exist. Therefore, the original premise for forming the Consortium was the protection of the environment and its enjoyment by a few people interested in building summer residences. The common goal was to have large stretches of this wonderful territory occupied exclusively by a few villa owners. Agreement on the fundamental principles for establishing the Consortium was easy. There was no concept, nor any questions, about the feasibility of territorial development. The strength of the romantic commitment to the Costa Smeralda® project was such that we did not even ask the simplest questions about how to live there given the lack of basic services. We never faced issues such as where water would come from or who would build the roads to ease access from Olbia to Porto Cervo.

The construction works at Porto Cervo. In the centre, Prince Aga Khan

The construction works at Porto Cervo. In the centre, Prince Aga KhanWe also did not question whether it was reasonable to think one would always have to take a ferry to reach Porto Cervo, or whether it was realistic to spend summer after summer without telephone communication. These were not concerns for these romantics, and everyone was confident that the beauty of the landscape would convince “someone” sooner or later. Consequently, the idea of creating a significant and strong leisure industry on the island was embraced as an innovative, perhaps even revolutionary, concept.

For many years, this concept suffered from the evident lack of credibility from local and regional authorities, and perhaps even at the national level. In those early years, questions such as: How many people, and from where, would want to invest in Porto Cervo to build summer residences? How much would they invest? For how many months would they use their properties? How much could they spend on their holidays, and how would they travel to and from Sardinia? — all went unasked and unresolved. At the beginning, there was no idea that the consortium area could one day become an integrated resort as it is today.

As this idea grew, another typical problem of Mediterranean tourist locations emerged: seasonality. Demand for transport, hotels, and sports facilities was strong for three months, marginal for another three, and nonexistent for the remaining half of the year. This meant investments could only be profitable for a quarter of the year. It took many years to organize the tourist season and marketing strategies according to market seasonality. The Consortium also faced strategic difficulties. The restrictive urban and construction rules, adopted by the founders to protect the area’s environmental characteristics, had to be acceptable to those interested in investing in Costa Smeralda®? Would they be acceptable to entrepreneurs, who were at least as, if not more, interested in profits than in environmental impact? The Consortium chose strict controls and maintained them, convinced that, when received as guarantees for investors, they would gain broad support. This choice has proven correct over time.

To answer the first part of the question about the role of the Costa Smeralda® Consortium in developing tourism in Sardinia: over these twenty-five years, the Consortium has been, and continues to be, the main promoter of regional tourism development. It launched this “new” industry, consistently supported and guided it, facing challenges as they arose. In these twenty-five years, it has identified and assessed potential, opportunities, and impacts on the local socio-economic system. It has also demonstrated capacity, maturity, and responsibility, planning development on a long-term basis, while acting as a key interlocutor with regional government and local administrations on tourism-related matters, as well as with relevant service and infrastructure organizations.